At First Sight

On an otherwise unremarkable day—the exact date is lost to history—in 1826 (or ‘27), the French inventor Nicephore Niépce set down his camera obscura on a windowsill and captured the view outside. Today, we recognize this image as the oldest surviving camera photograph. Gazing upon it, we might feel a sense of wonder and perhaps, also, a bit of romance. Of course, Niépce was a great scientific mind who had worked tirelessly to bring his vision of photography into reality—but I imagine he also had a touch of the irrational, of the fantastical. How else could a perfectly rational mind become so obsessed with the romantic idea of fixing time?

Nearly two centuries later, another hyper-rational (yet secretly romantic) person arrived in Niépce’s hometown in pursuit of a similarly far-fetched project. Natasha Caruana, the winner of the BMW Residency at the Nicéphore Niépce Museum, had been given three months to pursue any project of her choosing.

Caruana, an emerging artist, was well-known for an oeuvre that mercilessly questioned our views of romance. In one series, The Married Man, she dissected the dream of marital love by surreptitiously photographing married men who agreed to take her out to dinner. In another, Fairytale for Sale, she befriended brides who had put their wedding dresses for sale online, thus exposing the thin veneer of fantasy around “the big day.” In short, she was a born skeptic, a questioner, a doubter.

So it was with a bit of Niépcian good fortune that just three days before she was due to begin her work, she found herself at her own wedding day. But how? She, like so many others, had been struck by that irrational thunderbolt, what the French call “coup de foudre”—love at first sight. The long-time doubter had been converted. Besides changing her entire life, her planned project was also thrown into doubt. Would she still go to France? What would her project be about? She decided to push ahead. Like a blindly faithful lover, she arrived at her residency with no plans (not even a camera!) and lots of faith that, in her words, “things would work out.”

But even with romantic optimism at her back, Caruana had to figure out quickly what she was going to do. Again, Niépce called. After all, when Niépce was inventing photography, he was facing a largely scientific challenge, not an artistic one. This inspired Caruana’s approach. Although she was ostensibly delving into the greatest irrational mystery of all—the mystery of love—the atmosphere gave her an excuse to engage her intellectual side once again. Surely science, that unfailing means towards knowledge, and photography, the bearer of truth, would reveal an answer.

Yet when Caruana confronted her personal experience of love at first sight, she remained confounded. She began to attack the problem from all angles. She dove into a number of PhD dissertations, covering such topics as neuroscience, anthropology, attraction and mating. She decided to seek out other lovers in order to ask them about their experiences: Could this kind of love really last? Were their (and her) feelings really true? Ultimately, she did as she has done in the past: she picked up her camera and began taking photographs.

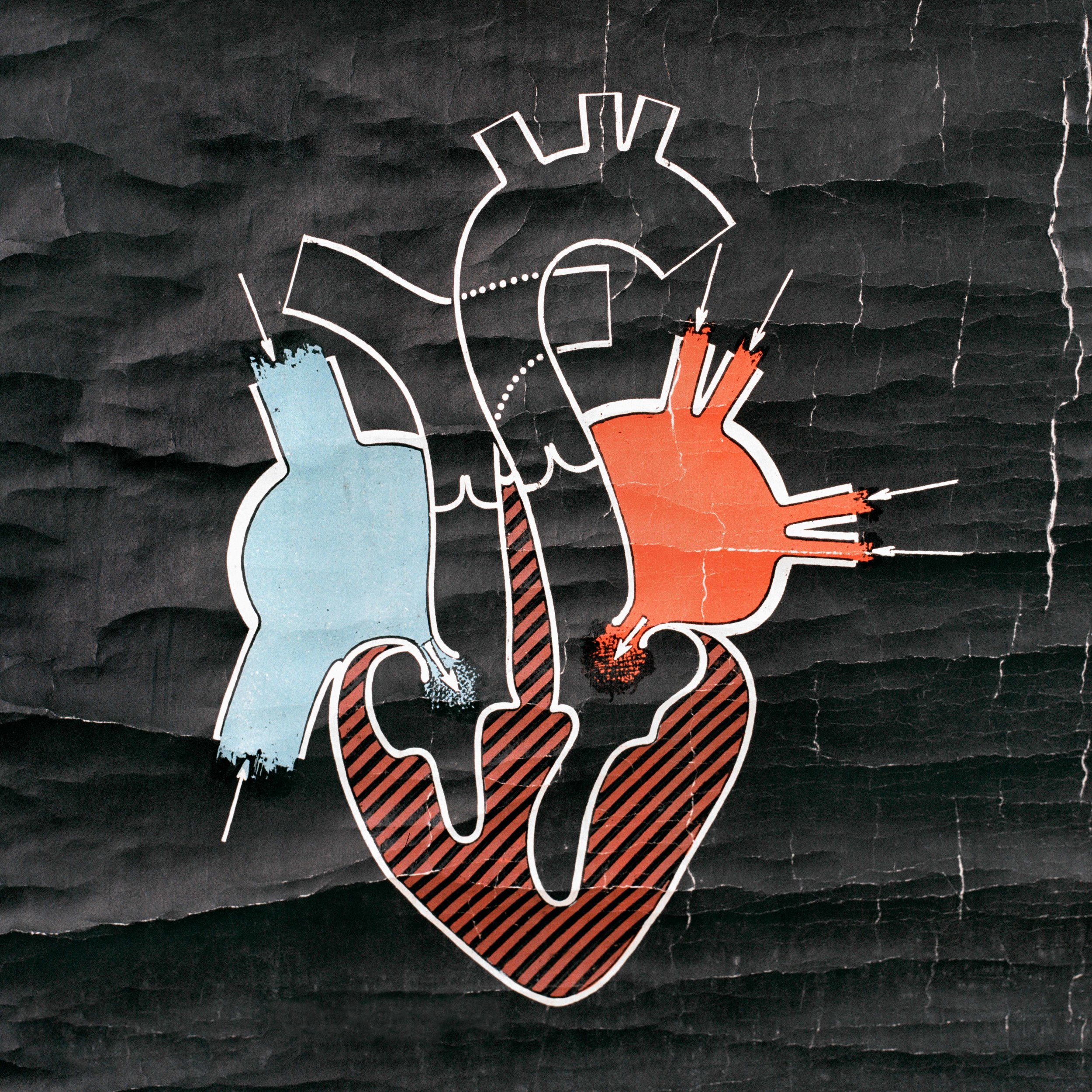

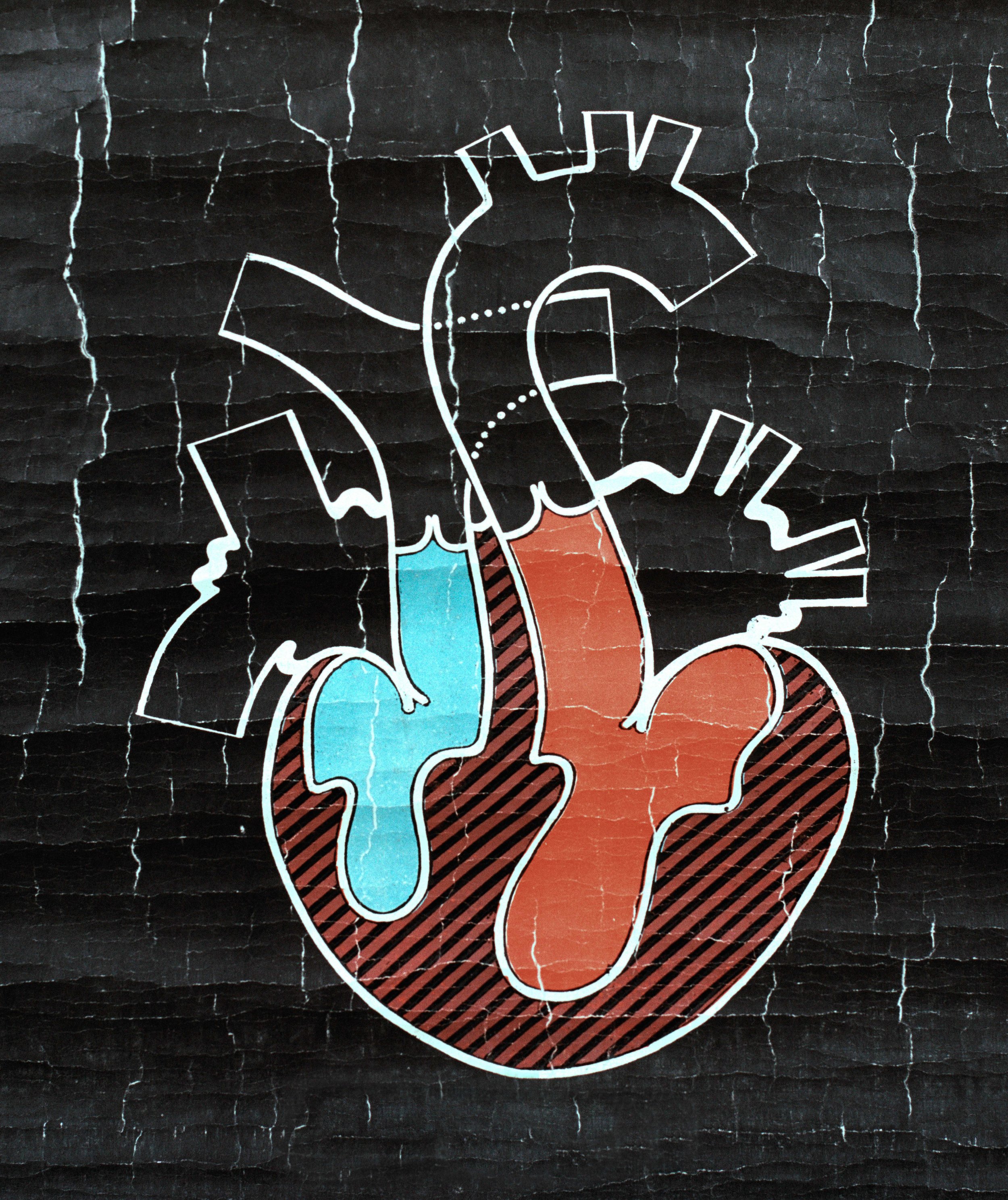

But how to create a visual expression of something that is, at once, so internal, so indescribable, so mysterious? Variety proved Caruana’s ally. She made portraits of lovers who were re-creating their own “coup de foudre.” But she also traveled to laboratories to photograph psychological experiments; she went to a strip club and shot it in the harsh light of day (to accompany a scientific study on the ovulatory cycles of lap dancers, of course); she even printed old scientific illustrations to illuminate the physical sites of our love—our nerves, our cells, our blood.

Yet for all of Caruana’s careful efforts, the project’s strongest moments came when she least expected them. As in any great romance, it was mystery, magic (and a bit of luck!) that proved to be her most reliable guides. For example, towards the beginning of the project, Caruana had been frustrated by her efforts to photograph scientific experiments. Aimlessly driving around the nearby countryside, she saw a group of scientists doing an experiment on the side of the road. She got out. She had found her subjects. Later, in an antique shop next door to the museum, Caruana found an amazing set of medical classroom illustrations (the ones mentioned above). They were original copies of drawings that had been used as official teachings of science across the whole of France. On the internet, these drawings costs thousands of euros. She found them for a pittance, just when she needed them.

But the most important instance of magic could be found in the completion of the project itself. When Caruana arrived at the museum, she had spent less than a week reading about love, in preparation. She arrived with nothing and was expected to produce something—something about love.

And so, like the best of love stories, things found a way of sorting themselves out. Of course, there were some freak-outs along the way—but what relationship doesn’t have its bumps in the road? As Caruana told me, “You just have to keep believing…”

Alexander Strecker